On this day, 106 years ago, eleven biplanes took off from the Italian North East for a 1200 km round trip to reach the capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Wien, and drop propaganda leaflets written by poet Gabriele D’Annunzio and author Ugo Ojetti.

At 5:30 in the morning of Aug. 9, 1918, eleven Ansaldo S.V.A. biplanes took off from a field at Due Carrare, near Padua in the Italian North East, for a daunting 1200 km round trip that brought them over the Alps and to the capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Wien (known as Vienna in Italian), to drop over 400,000 propaganda leaflets, in one of the most famous propaganda missions in history.

Together with the ten single-seater S.V.A.5 planes (so named after the two designers, Savoia and Verduzio, and the maker, Ansaldo), there was a single S.V.A.10 twin-seater biplane carrying the famous poet and soldier Gabriele D’Annunzio.

D’Annunzio, an ardent interventionist, had volunteered at the start of World War I despite already being 52 years old, and by 1918 had participated in numerous battles on land, sea (among them, the Bakar raid also known as the Bakar mockery) and in the air, earning multiple Italian and Allied medals and suffering injuries, including losing the right eye in a crash-landing.

Modern psychological warfare and the use of airborne leaflets were in their infancy during World War I, and D’Annunzio played an important role in the development of both. He joined the ranks of other famous literary talents at the service of wartime propaganda, like the British-employed Arthur Conan Doyle, G. K. Chesterton, Rudyard Kipling, H. G. Wells and Robert William Seton-Watson, but the Italian poet also joined frontline units and fought firsthand against the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Just a year before the Flight over Vienna, in August 1917 he participated in three daring night-time raids over Pola (the modern Croatian city of Pula) and later in October 1917 he joined a strike of the harbor of Kotor, conducted with Ca.33 biplane bombers. But D’Annunzio also pioneered the idea of dropping leaflets over enemy cities (unlike other Allied leaflet-dropping missions, usually aimed at frontline troops and trenches), with a less known raid in August 1915 over Trieste, at the time a major Austro-Hungarian port and naval base on the Adriatic.

The idea of a leaflet-dropping mission over the enemy capital of Wien had been long-harbored by D’Annunzio, and the raid was almost approved in the summer of 1917. Continuously delayed over technical problems, the operation was finally given the green light in the summer of 1918, but on 9 August was already on the third attempt, after heavy fog and strong winds prompted the cancellation of already departed missions on August 2 and 8 respectively.

On 9 August the weather finally cleared, and the eleven aircraft out of the original fourteen (three having been damaged in the previous attempts) of the 87th Squadriglia “Serenissima” (a name used for the Republic of Venice), bearing the famous “Lion of St. Mark” of Venice, were finally able to take off.

The group was promptly reduced to only 8 planes, as mechanical problems forced two S.V.A. to abort and a third plane, the one of lieutenant Giuseppe Sarti, to land in enemy territory. The surviving aircraft, including a specially modified two-seat biplane carrying poet Gabriele D’Annunzio (sitting on an what he termed the “incendiary chair”, a fuel tank field-modified to turn the single-seat biplane into a two-seater), pressed on.

Over Wien

Overflying the Alps and pressing on into Austria without encountering opposition (the only two Austrian fighters that spotted them, landed to warn the authorities but were not believed), the eight surviving biplanes finally reached Wien around 9:20 and dropped to around 2500 feet to release the leaflets.

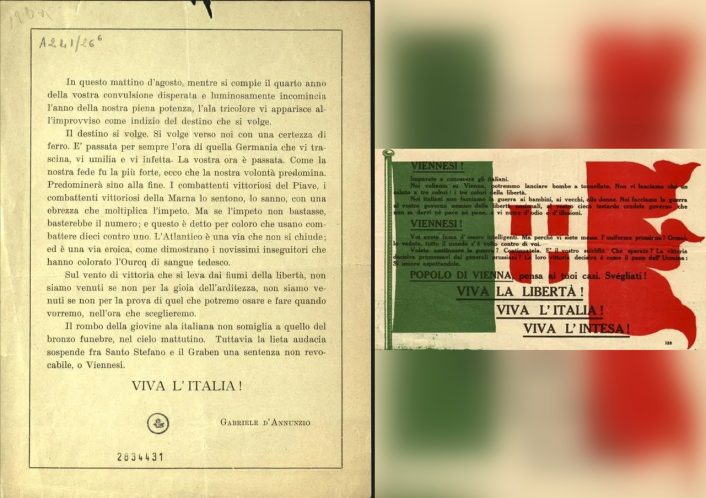

The eight planes released around 50,000 leaflets written by D’Annunzio in Italian in his poetic style, and over 350,000 carrying a more direct text written by author and journalist Ugo Ojetti and also displaying the corresponding German translation.

The leaflets by Ojetti ended with the words:

“PEOPLE OF VIENNA, think of your own fates. Wake up!

LONG LIVE LIBERTY!

LONG LIVE ITALY!

LONG LIVE THE ENTENTE!”

Having completed the mission, the eight airplanes departed for the return leg, again crossing the Alps and making a fly-over of Venice, where D’Annunzio dropped a message to inform the city authorities of the successful mission, and then landing back at the home base at around 12:40. The raid had great moral, psychological and propagandistic effects both in Italy and abroad, and was an important historical achievement in aerial warfare and psychological operations.

The “Lion of St. Mark” emblem of the 87th Squadriglia is nowadays one of the four emblems in the Italian Air Force coat of arms, along with the winged horse of the 27th Squadriglia (formerly 10th Squadriglia Farman of 1913), the prancing griffin of the 91st Fighter Squadriglia “Baracca” (known as the “Squadriglia degli Assi” because it was home to numerous World War I aces, including Francesco Baracca, Fulco Ruffo di Calabria and Schneider Trophy-racer and speed record-holder Mario de Bernardi) and the four-leaf clover of the 10th Bomber Squadriglia “Caproni” that used the namesake bomber planes.

Many of the S.V.A. biplanes that took part in the Flight over Vienna are today preserved in aviation museums in Italy.

Besides the S.V.A.5 replica at Volandia (a museum that also hosts many Caproni aircraft and has a simulator allowing visitors to fly as the pilot of the Ca.3 bomber), the two-seater S.V.A.10 used by Gabriele D’Annunzio is preserved in the museum in his villa on the shores of lake Garda, the Vittoriale degli Italiani, while the S.V.A.5 of 2nd lieutenant Gino Allegri is at the Museo Gianni Caproni at Trento and the S.V.A.5 piloted by major Giordano Bruno Granzarolo is at the Italian Air Force Museum at Vigna di Valle on Lake Bracciano.

Due Carrare, home to the field that hosted the planes, also has a S.V.A.5, preserved in the local Air and Space museum.

Another poet dropping leaflets over a capital

In a remarkable coincidence, another poet and pilot would emulate the exploits of D’Annunzio only 13 years later, and would do so over the Italian capital of Rome, albeit to a less favorable outcome.

Italian author and poet Adolfo Lauro De Bosis, whose father founded the literary magazine “Il Convito” that also published works by D’Annunzio, had been a Olympic-medalist (winning a silver medal at the IX Summer Olympic of Amsterdam 1928 in Literature with Icarus) and an early anti-fascist leader, co-founding the “National Alliance for Freedom” in 1930.

Further inspired by a leaflet-dropping flight over Milan by Giovanni Bassanesi and Gioacchino Dolci, who crashed on their way back to Switzerland, in the Autumn of 1931 he bought a small Klemm L 25 training plane nicknamed “Pegasus” and departed from Marseille in the early afternoon of 3 October.

After reaching the Italian capital of Rome undetected, he dropped over 400,000 anti-fascist leaflets over the city, the royal residence and Mussolini’s Palazzo Venezia, and after circling for almost half an hour over the capital, finally departed towards the sea but tragically disappeared on the return journey.